Ascent of the Matterhorn

The Matterhorn towers above Zermatt and this towering aspect owes something to the fact that it stands on its own. It catches the eye and very often seems to have smoke blowing off the top. Some air passage causes this condensation and localised streaming cloud pattern.

Matterhorn from the Domhütte

Photo: chil, on Camptocamp.org Derivative work: Zacharie Grossen, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

I’m not a mountaineer but I talked about climbing it on a skiing holiday with a Yorkshire couple, Chuki and Adrian Williams in Cervinia, Italy. We were staying in a very small Pensione and every evening we would try a digestif after dinner out of one of the bottles on the very top row behind the bar. There were a lot of them and it became a thing with us that we’d try and get through the lot. It took a few days to make an impression but we persisted and the barman kept a small ladder at the ready behind the bar, aware by midweek of the objective.

The very last bottle had a picture of the mountain they call in Italy, Monte Cervino. We decided the contents tasted better than anything else and thus fortified we set off to find the local girl from the ski office who’d arranged our visit, to see if she could tell us where climbers start from, to ascend the mountain.

The next morning we all walked on our skis through the woods behind one of the downhill skiing pistes and then on foot onto the veranda of a substantial chalet-style wooden building. Our guide had the key. She opened up and we entered a magic atmosphere of well-worn boards, white walls and wonderful black & white pictures of mountaineers, which went back many years. I had my head on one side at times trying to work out whether the man in the picture was upside down or what. The black & white pictures showed men with little round sun glasses like those of John Lennon. They had lined, smiley faces and sported canvas rucksacks, festooned with straps, holding wooden handled ice axes, ice screws, hemp ropes, crampons, water bottles and rolled tents; not a piece of plastic to be seen. The place was redolent of storytelling and camaraderie. The girl told us we should come in the summer and climb the mountain.

Breuil-Cervinia - Valtournenche - Aosta Valley – Italy

Francofranco56, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The idea of coming by train across the continent to the bottom of the valley and joining a party to make an attempt on the mountain stayed with me for several years. A major trouble was always that one had to give it a fortnight to get fit and acclimatise for the height. Weather is fickle in the mountains and room made in one’s calendar together with all the preparations could easily come to nothing. Many attempts could be wasted because of bad weather and each time the guide would have to be compensated for booking him but then never starting.

I decided things would have to wait until I retired, and it was also easier to go on my own to fit in with the short Matterhorn climbing season. The other decision was to attempt the climb from the Swiss side of the hill rather than Italy. They spoke more English, seemed better organised on forward weather intelligence and I had more occasion to visit Switzerland than Italy.

I had two attempts on the Matterhorn each time at the end of July, beginning of August, the best chance of a weather window. On the first occasion in 1993, I met with my Guide, Kurt Lauber and he told me he would take me up when the top of the mountain went black. At the moment it was white, indicating ice and snow on the top section; conditions for a serious Alpinist.

For altitude acclimatisation I did other 4,000m (13,123ft) peaks which were more suitable for the likes of me. I recall doing the Breithorn with John Guthrie, Lorne Williamson and Gilly Hamer-Hodges, led by Ulrich Inderbinen, while waiting for the head of the ski Schule, Felix Julen to take us ski touring on the Haute Route.

Now I did Castor, 4,228m (13,871ft) with guide Willy Taugwalder, Pollux 4,092m (13,425ft) with Roman Imboden and Rimpfischhorn 4,199m (13,776ft) with Ruedi Steindl. The latter was a longer climb of 6 hours as it starts from lower down at Flualp on the other side of the valley.

I was in disgrace as Ruedi woke me and then came back 20 minutes later to find me fast asleep again. Waking me once more he set off, so I was struggling to catch up. It was a grey cloudy day and I only came out of the cloud at the very top, literally the last 20m (66ft). The Matterhorn and the top teeth of other peaks were poking out all around.

With Matterhorn still closed, I had a few days left so I joined ‘Danny’s Circus’ to be taught to fly a Parapente. A Parapente is a banana shaped parachute. Wearing a harness to which the chute is attached you pull the thing up into the prevailing wind. Like flying a kite you stand staring up at the chute until you have the thing riding high. Then, happy that all is well, you run to the edge of the cliff top and keep on running. I am at everything a slow learner and first efforts at short glides on a high pasture slope invariably left me in a crashed bundle of body and chute. I got it eventually and the thrill of being aloft way above Zermatt able to manoeuvre for a sneak photo of the Matterhorn through my airborne legs was magic.

View of Matterhorn through my legs

from a Parapente chute

Then 'Control' started issuing instructions from a one way radio on my sleeve. Control was always anxious because the only landing place the authorities had allowed was behind the railway station. If one got the approach wrong the overhead electric train wires loomed up. I never managed a decent landing but hit the eidelweiss in lieu of the wires.

After a few excitements I qualified and have a Certificate to the effect that I am a qualified Parapente captain! I always intended to buy an old chute, carry it up to the top of The Craigs and beat the dog back down to the garden at Amat. One of these days I swear I will astound my friends by gliding into breakfast.

The mountain never went white so I had to come home and wait another year before going back to Zermatt.

On one Swiss visit, my then wife and I visited the Alpine garden set up many years ago by an English lady on the Schynige Platte near Winderswill. We travelled up on the mini rack railway and later walked down, a super day with marked flora and fauna changes at different altitude levels. The next morning she left at 5am to catch a plane home while I had a business appointment.

When I got to the airport to catch the evening plane I found I had my wife’s Passport, having given her mine when more than half asleep in the early hours. I worried whether she’d got away and airlines do not share their passenger lists. Finally I learned she had been allowed to board so I pressed successfully to do the same.

At London I was asked to step to one side for interrogation. I was lucky, recognising the CID man. I’d played squash against him, pulling his leg that the changing room at Trenchard House, HQ of the Metropolitan Police Service sported a sign on the wall indicating that anything left would be stolen for sure. Talking to my friend in his office, he told me there was a mafia crook on my flight but no excitement. London was just gathering intelligence and passing it on.

Only days later however this same officer was recovered from the end of the runway after an apprehended man had escaped custody and shot him, leaving him in a pool of blood. ‘Smithy’ was a very popular man and the Police look after their own. A large operation yielded someone in front of magistrates in the morning, reported as being somewhat the worse for wear.

My second attempt was in 1994. I went up to London and stayed in a flat near Victoria. On Monday I bought boots and arranged tickets. On Tuesday I took the tube to Heathrow with minimum spare time. A bomb alert stopped the train in the last tunnel; with the electricity turned off, we all had to jump down to the track, (which was quite a long way especially in the dark) and walk through the tunnel. When I jumped there was a squeak and I discovered that I had landed on a lady as black as a bishop’s hat.

After a quick feel around to orient ourselves she stuck my suitcase on her head and we held hands and made our way through the Stygian darkness. My new friend turned out to be a statuesque Somali called Kim working at Terminal 3 where she translated Arabic for Immigration Control. She had two teenage children and in reverse of the norm, she gave me her number, wanting to hear the outcome of my quest.

It was a good flight, caught because, like me, it was late. I took the train from Geneva, changing at Visp, arriving Zermatt at 8.50pm. I spent the night at the Bahnhof Hotel, a noted climbers basic hotel, owned by the mountaineering Biner family but removed to even cheaper lodgings in an outhouse of the residence Le Mazot, Roger Muther.

This had a room in one of the few remaining, extremely old, small wooden huts standing on large saucer shaped stones which in turn sat on stone plinths, a little way off the ground. All of this keeps out the rats. I guess it had once housed cattle but now this one had a single room and shower plus one feeble light bulb and a bit of old linoleum on the floor. It suited me just fine. It was a lovely moonlit night with the Matterhorn looking silvery and mysterious. There were lots of revellers in the street celebrating successful ascents of various mountains during the day.

Gornergrat Cog Railway, Zermatt

the first electric mountain train in the world.

The line opened in 1898.

Cable1, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The following day, Wednesday 17th August, I just couldn’t get started. I was up at 7.30am but failed to get going until 11am. I then started anew my acclimatising programme by walking up to the Trift mountain hotel above the station. As I passed the station I saw an electric engine named Mt Fuji at the head of a train from which copious Japanese visitors had just alighted and were having their photos taken. I sat on a platform bench and waited. 10 minutes later a workman unscrewed the nameplate and substituted another, ‘Matterhorn’. Could we do this in the UK? - Of course not.

It is a 750m (2,460ft) climb to Trift and when I got there I looked back in the visitor book and found I was nowhere near my last timing. It was now raining with deteriorating conditions. Nevertheless, I continued on my Wanderweg toward the south and came back to Zermatt via Zmutt and to my private hutte base with everything sodden. I ate too much and read in bed too late and finally dropped asleep about 1am.

Now, Thursday 18th August, a slow start as everything is covered in mist. Mrs Muther told me I should be doing the Mettelhorn so I set off about 10.50am forgetting extra clothing. On this occasion, I improved my time to Trift by 15 minutes which was now in sun and found a man sitting beside the onward path to Mettelhorn.

Mettelhorn mountain from west side, Switzerland.

Roylindman at en.wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

He turned out to be a delightful Swiss medic called Anwar Gern. Anwar was trying to overcome vertigo and asked if he could accompany me up the Mettelhorn. “Fine but I may be no help, I could be worse than you,” I replied. So off we set together. We met a Brit coming back who said he’d been unable to get to the top for want of crampons.

Over a beer that night we worked out that he’d been attacking the wrong Horn, the Platthorn. When all sides of the right mountain were becoming one point we crawled on all fours. Anwar wouldn’t look over and down but I found that I was OK and reported that if he wanted to catch the next train down to Visp he’d have to get his skates on.

Our timing of 4 hours improved by 1 hour, that which was painted on the Wanderweg signposts. So I was very pleased with myself and in the lovely weather too. Total walking/scrambling time was 7.5 hours and the 56 year old body was exhausted, especially my calf muscles. Anwar and I had dinner that night together and I met his family who had been in the Swiss watch-making business.

I contacted Petrig and his son Christoph who owned the City Hotel, Direction Sunnegga. They said they would take me on the Rifelhorn the following day, on the way up to Gornergrat, providing the winds were too strong for the helicopter party Christoph was scheduled to take elsewhere. I set my alarm for 7.30am.

It was Friday 19th August and I managed to make it to the agreed rendezvous point near the top of the Gornergrat railway on time only to find Christoph HAD gone in the helicopter. I consoled my disappointment with a second Früstück but eventually got going and walked to the Schönbielhütte at 2,700m (8,858ft) which took 4 hours and roughly 1,100 vertical meters (3,609ft), a total of 3,904m (12,808ft) to date.

The weather was fine, occasionally overcast, but obviously quantities of wind on tops. My left foot now had a blister on the heel and another inside the big toe – boring.

Willy Taugwalder, a direct descendant of the Whymper Matterhorn saga family is the keeper of this hutte but there was no sign of him. We came past here on the Haute Route and it offers the most wonderful view of Zmutt, Zermatt and an entirely different perspective of the Matterhorn and Zmutt glaciers.

The day took 7 hours in total and on my return I was more than ready for the shower. I found a note from Aurelia Biner of the Guides Office telling me she’d booked a training session on the Riffelhorn for the following day, Saturday. I hired a harness, had an early dinner and hoped the blisters would improve and some progress would be made.

Riffelhorn viewed from the Gornergratbahn, Riffelberg / Zermatt, Switzerland

Andrew Bossi, CC BY-SA 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

Saturday 20th August, a big effort resulted in catching the 0730 Gornergrat train. On parade at Riffel Halt and no guide appeared; I was standing like a lemon with the train just about to leave when a real Oldie came round the corner smothered in ropes. He goes off to buy a bottle of coke, somehow just knowing the train will not leave without him and so it proved. Called Rony, everything about him had known much better days. It suddenly dawned on me that I was about to entrust my life to this aged eggshell; but when we got down to the business he was excellent. I was the meat in a roped up sandwich, tail end Charlie being a young bespectacled Japanese who’d appeared out of thin air. Frail ‘Eggshell’ was intending to hold us both if we fell.

We went up vertical walls and then we went down them again. We crept round corners seemingly on fresh air above a vertical fall to the Monte Rosa glacier well below. I was completely spooked but Rony hauled us up, belayed us, lowered us and kept up a continuous burble relating to the crisis of the moment. “Keep moving”, “find the fingernail holds ya”, “lean out into abyss, ya ya”, “put the weight on ALL the bootie ya”, “trust the booties YA”.

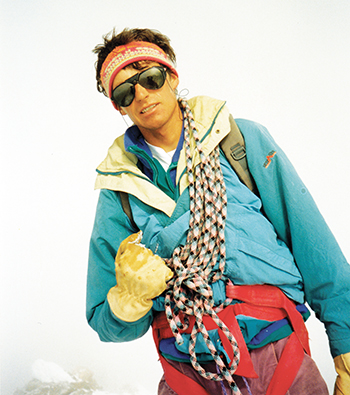

Christoph Petrig,

Jonny's Matterhorn Guide

I walked gently home with a headache and took to bed snacking on aspirins, but I was immediately disturbed by Christoph Petrig who came to see me to say I should meet him at the Belvedere Hotel tomorrow night for an attempt on the Matterhorn on Monday morning. He had information that there was a weather window coming but not a large one and that we were approaching the end of the season with chances tailing off if I turned down this opportunity.

That night I put on all the gear to make sure I had the hang of things and went on a practice around my bedroom.

I was doing rather well until I got stuck getting over the top of the shower at which point the landlady came in to investigate the muffled curses.

I had burnt my socks by leaving them too long to dry on the hot plate and so had an immediate shopping list for new ones and helicopter rescue insurance which I thought a good idea but which is non-refundable if we fail to start. By now I have an enormous blister on my left heel which had popped, exposing a great expanse of raw flesh. There was another cooking on my left big toe and the previous day I had had a severe attack of cramp in my right leg. So in the morning, I planned a visit to the church and more bits and pieces from the chemist.

After my daily training, I had until now, made my contact with the rest of the world by frequenting Elsie’s bar in the main square of an evening. If you were ‘available’ you sat at the bar and if not, in the body of the room. I sat on a stool at the corner of the bar with my legs hanging out hoping someone special would trip over them.

Somewhere along the line I made the acquaintance of a Church of England vicar from Malvern way. He was giving his time taking services in the tiny English St Peter’s church in the village for summer season sabbatical. We ended up dining together and finished our meal with an agreed pudding and two spoons. I had said I would turn out on Sunday morning and toll the bell for him. St Peter’s is a pleasant chapel well situated with an interesting quotation from the psalms painted on the wall above the altar.

“Who in His strength setteth fast the mountains

and is girded about with power:

To Him be praise.”

A friend, who disappeared climbing on or near the Dufourspitze 4,634m (15,203ft), is buried in the church grounds. His body reappeared about a generation later, identified by dental records but his climbing friend, like Lord Alfred Douglas lost on the way down from the first ascent of the Matterhorn, has not been found yet.

While I was tolling the church bell, a wreck of a man struggled up the path. He had recently looked at death on the Matterhorn. Part of an English climbing club, the party had reached the summit too late in the day. Night fell as they descended. Somebody slipped but this man held him, then he slipped himself, going over the edge. He looked to me as if he’d broken his neck, he was so lop-sided.

Somehow other members of the party had raised the alarm and very bravely, local mountaineers went up in the dark, but couldn’t manage to bring him in. However they did get a thermal blanket over him against the cold. In the morning a helicopter had effected a dangerous rescue.

The following day, I was about to do what he had done, ending the day, hopefully, in much better health than he had managed. However, at least he was still alive and if my informant was right had given his health to save a friend. I decided if I paced myself I’d be OK and that I’d probably never come again if I turned down this opportunity. The die was cast and I decided that what a middle-aged non-Alpinist should do was to keep active so I couldn’t brood.

After church, I packed up and got ready to leave. Slight butterflies as I was not quite as fit as I had been for last year’s attempt. I was rather annoyed to find the top clip broken off my new boots, so I had to tie both one rung lower. I took the cable car to Schwarzsee and walked up from there using a big rucksack holding some stuff for overnight including the ‘assault’ sack and then on to the Hornli Hutte at 3,298m (10,820ft). I was to sleep in the Hutte while my guide and others of his ilk enjoyed the greater attractions of the so-called ‘Belvedere hotel’, next door. Wish me well someone. It is 1330 hours.

While I had been walking up the main street of Zermatt I had paused at the plaque to Whymper, on the wall of the Monte Rosa hotel, which he’d left early in the morning of 14th July 1865 on his ninth attempt to climb the Matterhorn. This is by no means the highest mountain in the Alps but at that time was the only major one of note that had not already been climbed.

Inside this hotel is a room dedicated to the Alpine Club, the first mountaineering club, which was formed in London in 1857. Close by is the memorial of the club celebrating 150 years of friendship between Zermatt and the Alpine Club, pioneers of Alpinism.

Plaque to Whymper on the wall of the Monte Rosa Hotel

‘Edward Whymper, 1840-1911

On July 14, 1865, he set forth from this hotel with his companions and guides

and completed the first successful ascent of the Matterhorn.’

Roland Zumbühl (Picswiss), Arlesheim (Commons:Picswiss project), CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

I was so excited I never slept a wink that night. Mind you there were German speaking aspirants coming into the wooden floored dormitory all the time, seemingly shouting, “SSSH peoples sleeping.” There was also lightning and thunder. I lay on the spartan bed and conjured up a picture of Whymper and his party in their bivouac hoping to be the first to ever reach the top the next day.

At 2am we were all getting up and buckling on the gear we’d checked and rechecked the night before. No washing or shaving just a piece of bread and jam downstairs and then out into the night, with head torches on, looking for one’s guide along with the others doing the same amongst the scrum of rucksacks, coiled ropes and ice axes.

My man Petrig tugged at my harness to see it was correctly tensioned and in no way twisted. Then he clipped a loop of his rope into the carabiner on my belt, and tied and tested a figure of eight knot. We shouldered our packs, adjusted bonnets (no hard hats by tradition at that time), tested the firmness of the strap holding the head torch, put hands through the loop on individual ice axes and were ready.

There in the background was the target, almost black in the midnight blue sky with some unseen hand beginning to build a Christmas tree of fairy lights up the face. The youngest, quickest went first and we were somewhere in the middle.

This gave a minute or two to rub one’s hands before donning the soft chamois leather gloves which would be finished by the time we got back, assuming we did. A bit of stretching, a muttered OK and team Petrig/Shaw engaged bottom gear and set off.

22nd August 1994 3.30am.

It was a short walk to the base of what I call the podium on which the mountain bulk stood. The method was simple. When the incline got severe, then the Guide went up, tied himself to a rock and signalled me to come up with a tug on the rope. I would climb up to the guide knowing that if I fell he would hold me.

Next, he would see that I was secure, usually facing into the mountain and he would climb again to the length of the rope. Eventually we came to the Solvay Hutte at 4,002m (13,130ft). This is an emergency escape refuge for those overtaken by weather or injury. The incline of the mountain is sheer at this point and the old fingers get tested as one pulls the body up and searches with the climbing boots for something to take the weight. There is no danger of vertigo as one can see little and there’s no reason to look down, all concentration being on what the head torch tells one is the next piece of rock to overcome.

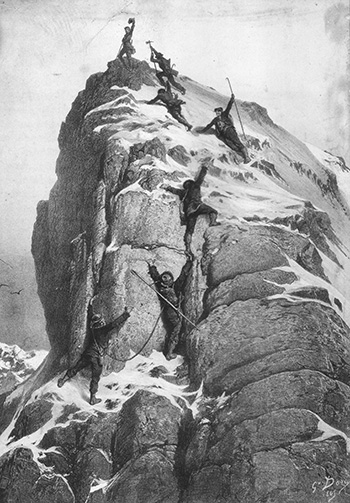

The first ascent of the Matterhorn was made by Edward Whymper, Lord Francis Douglas, Charles Hudson, Douglas Hadow, Michel Croz, and two Zermatt guides, Peter Taugwalder father and son, old Peter, and young Peter on 14th July 1865.

The first ascent of the Matterhorn (drawn by Gustave Doré)

Gustave Doré, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

He had started from the Monte Rosa hotel and they camped somewhere near the Hornli Hutte, a bit higher perhaps. Then Joseph Taugwalder who had helped porter impedimenta up to the site, returned to the village. They started the next day at 5.30am and by 6.30ish had reached 3,901m (12,800ft) and by midday 4,267m (14,000ft). After a rest and much zig-zagging from one side of the ridge to the other they reached the top at 1.40pm.

They began the descent after an hour on the summit. During that time they threw rocks down the Italian side to tell a rival party coming up that they’d made it. They erected a small flag with someone’s shirt and left their names in a bottle.

Michael Croz led them down followed by the weakest member in terms of experience, Hadow, then the Rev. Charles Hudson, Lord Alfred Douglas and Old Peter Taugwalder. Whymper had dallied on the top sketching but then he and the young Peter Taugwalder caught up with them as the leaders reached the difficult bit.

Around 3pm Lord Alfred asked these two to get on their rope as he feared old Taugwalder would not be able to hold if someone slipped.

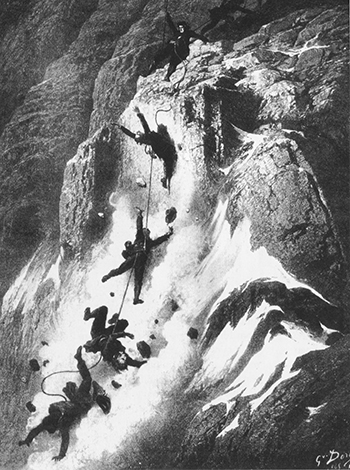

Disaster strikes just after the first ascent of the Matterhorn

(drawn by Gustave Doré)

Gustave Doré, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Something caused one of Whymper’s team to lose his balance and it would not have been Michael Croz, a very well respected mountaineer of his day who was leading the descent. That someone, probably the least experienced Hadow, would have fallen into Croz and taken him down with him. There would then have been a domino effect with each falling body making the total weight more than the next man could hold. Lord Douglas, Hudson, Hadow and Croz were killed falling straight down the north face.

In the record of what Whymper recited later, repeated by Mark Twain in his book ‘A Tramp Abroad’ in the 19th century, it seems Croz had to turn round and place Haddow’s feet one at a time. At a crucial moment, Haddow slipped into him when he had put aside his ice axe. The whole thing happened in a couple of seconds with all four dislodged.

The rope broke between Douglas and old Peter. When the forces hit him and Whymper, they had already heard the cries and braced themselves with no slack between them. The four fell some 1,219m (4,000ft) and the body of Lord Alfred Douglas has never been recovered. The rest were so stunned that no progress was made for a couple of hours. Eventually they fixed rope to secure rocks and let themselves down a bit at a time cutting the rope as they reached places they could hold, until they had passed the worst spot.

At about 6pm they were able to get onto the easier trail they’d left in the snow on the ridge and could believe they were safe. Old Taugwalder was subsequently accused of having cut the rope. Whymper said that even if he had wanted to, the tragedy happened so quickly he’d never have had time to do that and would not have been ready and braced when the load came upon them.

The disaster would have taken just a couple of seconds to be out of control. Then the rope broke and three stunned white-faced and powerless survivors were left unable to do anything for some considerable time. I was so pleased not to be sharing the rope with so many.

In 1865 there was a court of enquiry after the first ascent and disaster. The survivors were accused of cutting the rope but no such thing was proved. However Taugwalder senior was somewhat ostracised in the local community and left the village for a number of years. Whymper took himself off to Greenland for something like a decade. By all accounts he was not a very popular person.

Matterhorn standing proud of neighbouring peaks

The Matterhorn was one of the last 4,000m (13,123ft) peaks to be conquered. The much higher Mont Blanc had been climbed years before.

I felt stimulated that I was following in Whymper’s footsteps. Although I hadn’t slept I was going well on adrenalin and so, up and up we crept until quite suddenly, instead of the beginnings of a lovely dawn sky, we found ourselves in a snowstorm with increased wind, August for goodness sake! Petrig found a minute platform. We took off our rucksacks amongst some sheltering rocks and began the business of putting on the crampons and waterproof windcheater.

I wore my Ganton Golf Club top; from now on we’d be walking on steel teeth and I would need to walk slightly differently so that I didn’t catch an inside tooth in the other trouser leg as I walked that foot forwards. Any sudden jerk, especially in wind and lacking any horizon for my eyes, could easily cause me to lose balance.

Now in the snowstorm that morning there appeared in my face, a bearded fellow I knew, a ski mountaineer from above Sierre, Serge Lambert. I’d taken skiing instruction from him while on a Reps course and skied with him several times. “Hello Jonny how are you?” came from the beaming face, framed in the torchlight. I hadn’t seen another soul until that moment and later learned that Serge’s client, together with several others had turned back at this point.

He never mentioned that of course. If he had told me a number had turned back and, knowing him much better than I knew Petrig, I might have been worried and then sorely tempted to opt out. Instead Petrig and I carried on, all senses concentrated on the job in hand, whose pace was dictated by me but interrupted by the guide’s frequent “Come on Jonny,” encouragements which had started within half an hour of leaving the Hutte.

Fixated on the rope in front of my nose I was aware of going left-handed and round the distinctive bump one sees in the pictures of the Hornli route and little else. There came a moment however when we squeezed through a short fissure in the rock.

Here we had to make way for airborne crampons coming down to my face from above. We were being passed by those who had started first and were now on their way down for there is very little room on the top ridge. I braced myself against the rock, brushed crampons away from my forehead and helped guide them towards a suitable rock foot-hold.

There was now a powdering of snow cover but no chance of ice forming. I was head down trying to think of something other than the endless uphill grind.

It was my rule not to look at my watch as I had found when ski touring that looking too often was very disappointing; one seemed to have made so little progress. Grinding along ever upwards in the cloud with “Come on Jonny,” ringing in my ears every few minutes I started to think again about Whymper on his ninth attempt.

With all this stuff going through my brain I was taken by surprise to suddenly hear Petrig say: “Stop Jonny.” Then my face came up from my boots and I made an exasperated rude comment to Petrig along the lines of “All you’ve said for the last few hours is ‘Come on Jonny,’ why stop now?”

Jonny with his guide on the summit

“If you take another step,” he replied, “you’ll be in Italy for breakfast.” It sank in slowly as there was nothing to see through the cloud; but with a broad grin Petrig took off his glove and offered his hand.

The clouds parted somewhat and my aching limbs felt immediately quite unsteady at the sight of the view down below. Ever so carefully, with his guidance, I edged to a bump of rock upon which I could sit down and there enjoy a swig of cold tea.

Tea at the top

Slowly a couple of shapes dimly materialised, one was the cross on the top and then the next person up, an American. “Could I take his picture?” Both his children had turned back, the one with the cine and the other with the camera. I did as he asked as he held aloft a rolled poster advertising his company “Available For All Realty Business, Ring Toll Free this number, Matterhorn for Sale.” I don’t think either of the two guides present was amused.

New bronze statue of Madonna on the summit,

just below the metal cross

The American pressed to be allowed to purchase the camera and if not, then the roll of film, right there on the spot. I wouldn’t oblige as Petrig and I had taken pictures but said I’d see him at his hotel tomorrow.

Petrig decided we’d leave before any more people arrived as half a dozen is about the limit on the top.

The next day I met the American and he offered me the chance to be his guest on the Royal Scotsman train from Edinburgh to the Kyle of Lochalsh but unfortunately the dates didn’t fit.

It would have been fun as there is no more magical line in the British Isles.

They say that when you climb the Matterhorn the difficulties start on the descent, as Whymper discovered. Now I was to be the leader and instead of avoiding the drop with face turned into the rock I needed to step boldly toward it as though I was a somewhat light-headed Hamlet. The action is to roll the weight forward to depend on those two front, slightly splayed out spikes, of my crampons. These crampon spikes were designed to stop me pitching over and away into the ether; but until one has faith in them the tendency is to lean back away from the drop which left one relying on the two small spikes on the heel, not a good idea.

The cloud cover would now be a most helpful comforting aid, but, on cue to mock my thoughts, the clouds parted and there was the abyss opening its arms towards me. The ice axe as a walking stick now came into its own. I held it upside down and was able to stick the spike on the end into the rock so that it acted like an extra leg to prevent me falling sideways. If I slipped, the drill was to flip over, grasping the handle again, and sit one’s whole weight on it with the spade end digging into the surface. You can see the actors doing this at the start of the film ‘Seven Years in Tibet’.

Looking down from the Matterhorn

I was very aware that in putting one foot in front of another I had to be extra careful to avoid the spike of the back foot crampon catching my trousers as I pushed it forward. There was a bit of wind, not much but just enough to make me feel very wobbly on those first few steps, keenly aware that if I fell at the top, the fragile confidence would evaporate.

Petrig did not allow any loose rope. I had to pull it out from him like drawing an air hose out of its coiled container at the garage. This was very comforting and after those first half dozen steps belief flooded back.

Only when the rope was fully extended and I had to stand still without support, while Petrig came down coiling his rope, did I feel a little giddy as though a good puff of wind might just take me away like blowing the fluff off a dandelion.

Petrig arrived, belayed the rope round a small knob of rock and lightly told me I was doing fine “Take her away chief,” he said as though he was just patting the dog and I suddenly felt great.

The clouds parted some more, the temperature went up, the sun appeared, Driver Shaw eased the regulator open to allow the wheels to turn without skidding and we were away from top shed and out of gasworks tunnel.

Now, the repetition of these sequences was wonderful. Apart from having to squeeze past those coming up at the usual place, without stepping on someone’s head, I was able to murmur “Good morning, not far now,” smile and so pass on.

Back at the Hornli Hutte

with Christoph Petrig and Serge Lambert

Back at the Hornli Hutte there was Serge and a wonderful can of beer. The three of us had a good chat and then we parted as I preferred to continue on my own, chewing the cud and feeling hugely tired but wonderfully elated.

Any further thoughts were swamped by tiredness. By the time I was back in my little den I could think of nothing but a shower followed by sleep.

I could not undo my boots; the knots covered in rock dust seemed impervious to my attempts to loosen them. “OK, well stuff you,” I thought and stepped into the shower still dressed in boots and trousers. There, I just let this warm trickle of water cascade over me for an age and much later, passed out on the bed.

The next morning I didn’t go to my usual café where I could read an American paper in English and enjoy my good value breakfast deal. I went instead to sit outside on a veranda on my own with orange juice, coffee and a croissant looking up at the mountain and wondering how the hell I’d got up that.

It was just fantastic to sit there and absorb. I drank in the atmosphere, just a wonderful feeling of re-jigging my life which had been one-track-minded for some time. Then picking up on life’s necessities, I wandered across the road to get enough money to get home. I proffered my card into a bank ‘hole in the wall’. There was no interaction - nothing asking for ID - just no response, just nothing as if I’d not been there. The card was peremptorily swallowed.

I knocked on the door of the bank but my tapping received gestures from within to read the CLOSED sign. Like a Gresley Pacific safety valve deciding to blow off steam, something went ‘ping’. I hammered on the locked door. Those inside made more exaggerated ‘Go-Away’ gestures. I took off a shoe and started a drum roll on the door.

A very angry man appeared and said he was going to call the police. I told him his machine had gobbled my card, I had no money, he had it all, I wanted to leave his wretched country and if he called the police I would tell them he was the problem and demand representation from the British Embassy in Bern to sort him out.

Very slowly he told me that I had not proffered a card to his excellent machine and possibly broken it and he would be charging me for having someone come out and repair the damage, to that and also his door.

He insisted he was not able to open the machine but eventually he managed it and there was the card which he examined very closely with no comment or apology. I presented it again in his presence and drew out what I wanted.

I must have forced it in too quickly he announced - still my fault. I told him that in my experience it was easier to climb the Matterhorn than get money or service from his bank.

Before leaving Zermatt, I took the opportunity to visit Ulrich Inderbinen. When one visits any Swiss mountain Hutte, like the Hornli, there is always a list on the wall of all the active mountaineers and ski instructors with date of birth and ski guide number. There one saw, until recently, Inderbinen born 1st January 1900, Guides number ONE. I had climbed the Breithorn 4,000m (13,123ft) with him, around 1975. He had seemed a very old man then, but now, so many years on, he looked exactly the same.

I bought his book ‘As Old as the Century’. He was, of course, a walking encyclopedia having lived his whole life around Zermatt. In the 19th century, only 369 people lived, in some poverty, in Zermatt with women in particular dying young. Only when the railway got to Zermatt in 1891 did things begin to improve and then the railway only worked in the summer.

Then in 1898 came the world’s first mountain electric train from Zermatt to Gornergrat and the British started to arrive. The opening of the world’s longest railway tunnel at the time, the Simplon, in 1906, brought an immediate influx of Italians. Then WW1 closed all the new hotels and poverty returned.

The tourists didn’t come back until 1920 after influenza had taken a substantial cull of the indigenous population. Ulrich reduced the risk of contagion by riding the train standing on the step outside the door. He decided to change from being a farmer to being a mountain guide but had as yet climbed nothing. To put that right, in 1921, he decided to go up the Matterhorn with his sister, Martha and a friend who also brought along his sister.

They borrowed ropes and candle-lit lanterns and started at 2am having the mountain to themselves.

Struggling to relight their candles at times, they all made it and eventually from 1925 Ulrich began to attract his own customers leading to over 50 years of mountain guiding plus the new business of skiing.

Skiing took off when the railway finally started a winter service giving Ulrich additional employment. He suffered a broken fibula on one occasion while on the mountain and had to get down on his own which he did by tying his skis together and sitting on them; an amazing guy.

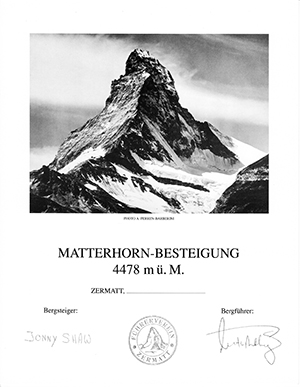

Certificate

LEGAL INFORMATION

The information and material on this site is provided in good faith for general information only and no part shall form any part of a contract. Amat Estate and its agents assume no responsibility for the accuracy of any particular statement and accept no liability for any loss or damage which may arise from reliance upon the information contained on this website. Links to other websites from these pages are for general information only and Amat Estate and its agents accept no responsibility or liability for access to other material on any website which is linked from or to this website.

© 2021 amatsalmon.com