The Clement

This 1903 French car was made in Paris. My father, Geoffrey Shaw, found it under logs at the back of a garage in Yarm, North Yorkshire. He was told that it had been bought new by a wealthy bookmaker, who was involved in an accident and consequently decided never to drive it again.

Car manufacturers, by this time, had learned how to make the complicated differential, which split the power between the back wheels as they turned through different arcs of a circle, when going around corners. However, the brakes depended upon cables which were much more difficult to compensate for, when the front wheels were hard locked one way or the other. Consequently, cars just had rear wheel brakes, until hydraulics replaced cables.

The Clement as found under logs

My father bought J379 and got it going again and I recall happy Rallies here and there in the UK. One day, we broke down as the float had sunk in the carburettor. Father bought the contents of a little boy’s mouth, the hole was stuffed with chewing gum and off we set again, with sometimes, even my father jumping out to join the passengers pushing and running alongside, while it chugged uphill.

My brother, Kippy, inherited it and he together with his son, Ben, have restored it beautifully. The manufacturer was Clement and the maker soon joined with others and certainly there was a Clement-Talbot. The French and Germans were ahead of us making petrol cars. The first one sold in the UK was a Renault, arriving in Hampshire by train, around 1895.

Out for a drive in the Clement

Looking at myself, hanging on the running board, the picture must have been taken soon after WW2. The girl in the hood, Jacky Woolcock, whose family lived with us after the war, and myself are the only two still alive. She became a GP and lives near Shoreham where there is a small aerodrome.

By coincidence, my Prep school was at Seaford and my father had a tiny Czech-made plane called a Sokol and used to collect Kippy and me from school and fly us home to Nunthorpe, Cleveland – close to Colin Harrison and Frank Debenham. We used to navigate by railway lines and find a Gresley A4 at full chat to follow and wave to the driver. The plane was parked like a speck of dust in the corner of one of the vast hangars at Thornaby aerodrome where my father had taken over as CO of 608 Squadron Auxiliary Airforce, which flew Lockheed Hudsons of Coastal Command after his friend Geoffrey Ambler moved to 609 Squadron Auxiliary Airforce in West Yorkshire (Church Fenton).

I didn’t know my godfather, Geoffrey Ambler, in a cognitive sense as he disappeared shortly after my birth until he was demobbed around 1948. So this has somewhat morphed into a Christmas Card as I struggle to learn more about him. The friendship between the two Geoffrey’s probably developed due to them both being engineers and their shared love of flying.

Geoffrey Ambler (front row left)

Photo: Clare College, Cambridge

Geoffrey rowed boats at Shrewsbury and continued to do so at Cambridge where he was in the Boat Race 1924 – 1926, all won, and President of the University Boat Club 1925/1926. As he was a tall man, he was probably Stroke. I spoke with Jonny Towers, who played Jonny Thin to my Jonny Fat and Guthrie’s Jonny Rucksack on holiday learning how to wedel (linked turns) in St. Anton in black and white photo days. That was when the platform bar was best value for heat, beer, schinken and rosti. He tells me that Geoffrey Ambler’s family, whom CPHM knew at Ilkley, have sadly all died.

The two Geoffreys joined the RAAF on its inception in 1925, the brainchild of Lord Trenchard (the ‘R’ was only conferred after the war). He envisaged a corps of flying businessmen who would be useful if we ever got into another war. On one occasion they flew in formation to London, took girlfriends out to dinner and a Show before re-donning goggles and flying on to the TA camp by compass, hand signals and the lights of London.

Called to London by Air Minister Viscount Thurso (Churchill’s 2 i/c of a Scots battalion in WW1 and an old friend), Geoffrey was given the Air Security of Scotland.

Asking about resources, he was told to do the best he could, as every RAF man and machine was earmarked for ‘A big Do in the south east’.

Viscount Thurso

Geoffrey went to see the Admiral at Scapa Flow who was not helpful. So he took over a farmhouse with a view of the Flow, installing an Observer and hotline. He calculated that Germany would not attack until it had annexed Norway, assembled bombers and made high flying spotter plane flights to locate moorings and pick a suitable weather window for a ‘Pearl Harbour’ style mission.

He accordingly set up forward airfields midway between Scapa and coastal Norwegian airfields and ‘acquired’ a suitable Spitfire and pilot able to reach the reconnaissance plane which was likely to be a four engine FW Condor, which could, without guns, overfly a Spitfire. (The early Spitfire’s rate of climb performance tailed off at altitude.)

He calculated that, provided radar could see the moment an aircraft had taken off and turned toward Shetland it would be possible to calculate the rate of climb and from that decide whether it carried guns or not. If it did, then it could be intercepted over the sea by other more vintage fighters.

If not, then Biggles would have 15 minutes to get airborne and grind up above 20,000 feet and when the reconnaissance plane got to the forward airstrip, it would still not be able to see the Fleet. Biggles could then be vectored very close by radar to deliver a deadly attack. One of the forward airstrips, Scatsta, was close to the place where the BP Sullom Voe terminal was subsequently built and was ready for fighters in 1940.

Geoffrey relied for Intelligence on the Observer Corps (later becoming their Commandant) and Norwegian fishing boats (Shetland Bus Service who took agents in and out of Norway). He engineered the key of a large alarm clock to release the damper on a stove to give himself a ‘brew-up’ ready for anything at 5am. Surprise was his trump card and little was written down. I find it interesting that RAF Scatsta remained active until June 2020. This and the flying boats using the Flow were able to harass Axis shipping and search for U-boats with radar able to detect periscopes.

MacRobertson Air Race Poster

My father took part in the UK to Melbourne Air Race in the 1930s and back from that, flew his German girlfriend to the Oban Ball. (I might have been German). Her father put a case of his own vineyard wine on her lap for the journey. The MacDonald Laird with whom they stayed, reciprocated with a case of whisky for the return flight which must have been truly uncomfortable for the lass, especially as the plane was not ready to fly at the end of the field and had to be jerked over the fence at the point of the stall continuing the take off in the next field.

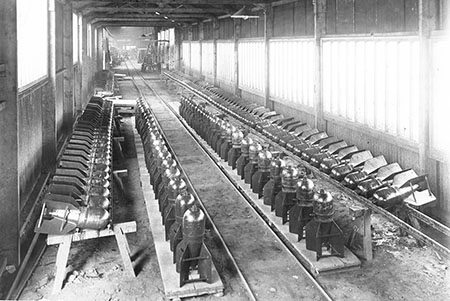

My father left his brother Roy making cast steel bomb casings in the family foundry and joined Coastal Command hunting U-boats. He was in a position to help my godfather as the Command had a base for flying boats on the waters of the Voe. Later, my father used radar in these machines (his favourite was the American PBY Catalina) to locate U-boats or periscopes by night in the Straits of Gibraltar.

Bomb Casings at Shaw's Foundry

Twin engine Comanche - J. G. Shaw

My Pilot’s Log tells me I flew twin Comanche G-SHAW with two engineers to Sullom Voe on 12th Dec 1979. There was a rush to get the new oil terminal finished and they demanded someone there instantly. We arrived in the gloaming and had to loiter as debris was swept off the runway from the plane in front. I wasn’t sure what that meant, but noted the absence of trees, allowing me on ‘Finals’ to aim across the centre line of the runway with a wing down into the big cross wind component. I stayed with the plane, virtually tying it to the Control Tower as 80mph winds were forecast. Inside the tower, I found a faded photograph which I was sure included my godfather. This must have been one of Geoffrey’s forward airfields.

Being cold, I took myself for a starlit walk down a now foggy, disused runway which would have been so preferable for my landing. I came without notice on why the runway was shut. A large modern building sat near the end of it; it was so odd to find it in the middle of nowhere in the night. I peeked through a lit window; a big man with a cigar was surrounded by large tape recorders. Maybe he listened to hydrophones strung across the sea toward the Faroes recording Russian submarines going to or returning from the Atlantic. It seems that Scatsta held long term secrets.

After the Battle of Britain, Spitfires became available and the Germans moved their bombers to the eastern front. Geoffrey then organised the squadrons that protected the main cities. He transferred to the RAF, got someone to promote him, operated from Wick and later became an ADC to the King. Respect enabled him to influence a cabinet plan to develop fuel injection from scratch. “Too slow,” he urged, “copy the excellent German system, tried and tested in the recent Spanish civil war”. His contribution was to strafe a German bomber until it landed on the beach, get the crew out of sight, strip the engine in the farmhouse and with a draughtsman, make exact drawings, to allow the system straight into production. He obviously had a mind like Tilly Shilling OBE, who solved the Spitfire’s Merlin engine problem - cutting out when its carburettor starved the engine of fuel in negative-g dogfights. A disc with a precise hole restricted fuel flowing away from the engine due to centrifugal forces. Dubbed ‘Shilling’s Orifice’, the problem was fixed instantly to the dismay of ME109 pilots.

Spitfire LF Mk IX

Attribution: By Bryan Fury75 at fr.wikipedia CC-BY-SA-3.0

I’m indebted to the Lord Lieutenant, Sir William Bulmer, who told us in Geoffrey’s 1978 Thanksgiving Service in Bradford Cathedral that when 609 Squadron were about to receive Spitfires, nobody in the Squadron had flown one. So he collected the first himself, reading the book as he flew it away. He trained himself and then his pilots to fight with it. When no pay arrived for his pilots, he arranged for his bank to pay them, becoming the only officer to have his own airforce. Demobbed in 1948, in his last leave, he qualified on RAF Meteor jets, the first AVM to do that. Back in Bradford, he invented and patented the Ambler Super Draft which allowed huge advances in Spinning Jenny performance, another AVM first.

Only in his latter days, did I have the pleasure to get to know him a little when he would visit my brother to discuss pieces for his Super Draft device and their shared sailing interests.

At his Service I was amazed at the number of Rolls Royces of all ages outside the Cathedral. Things are different in the West Riding, where it seems obligatory to have a Roller somewhere in the garage.

LEGAL INFORMATION

The information and material on this site is provided in good faith for general information only and no part shall form any part of a contract. Amat Estate and its agents assume no responsibility for the accuracy of any particular statement and accept no liability for any loss or damage which may arise from reliance upon the information contained on this website. Links to other websites from these pages are for general information only and Amat Estate and its agents accept no responsibility or liability for access to other material on any website which is linked from or to this website.

© 2021 amatsalmon.com